High above the desert south of Phoenix, Arizona, dozens of piston airplanes from countless flight schools occupy the same congested airspace at any given time. Pilots of all levels, from student pilots to advanced instructors, come to train in the Phoenix Valley to hone their skills and build time toward their careers in this hotbed of flight training activity. But what happens when all of that traffic converges on the same initial approach fix (IAF)? Welcome to the Stanfield Stack.

Training in some of the busiest airspace in the world

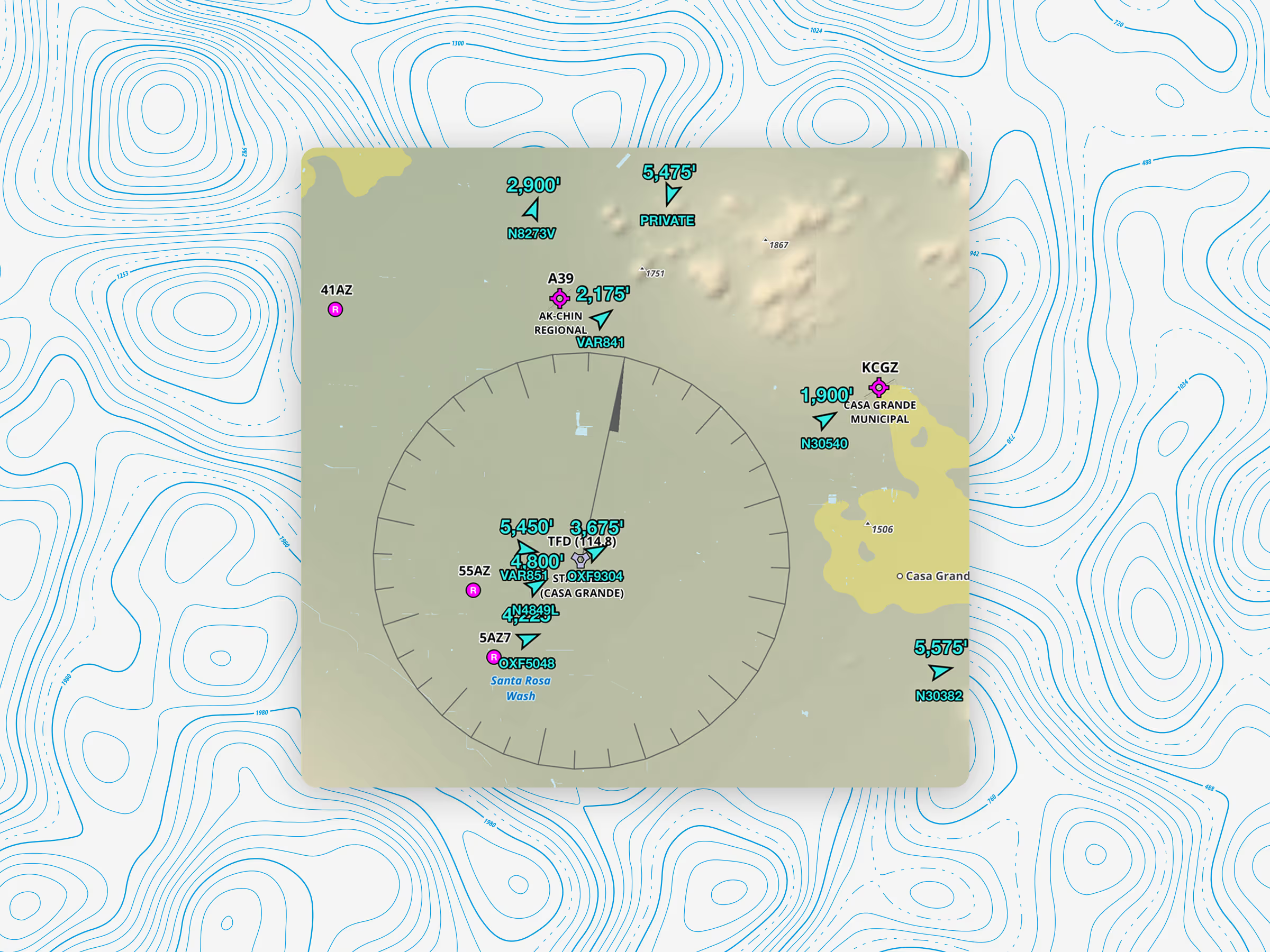

About 20 miles south of the Phoenix Valley, Casa Grande Municipal Airport (KCGZ) and the Stanfield VOR (TFD) are a pair of heavily trafficked general aviation landmarks. Casa Grande is an untowered airport that hosts a wide range of activity, from aerial firefighting training to parachute operations, and features multiple instrument approaches originating from the Stanfield VOR roughly eight miles to the west.

With its close proximity to the Valley and its position on the outer edge of the Phoenix Bravo airspace, Casa Grande is close enough to make for an easy training flight while offering multiple instrument procedures. It’s not uncommon for the airspace around Casa Grande to fill up early and stay busy all day as students and instructors literally line up above the VOR, waiting their turn to shoot an approach.

To help minimize the risk of midair collisions in this particularly busy area, the Arizona Flight Training Workgroup created an unofficial and optional procedure that provides guidance for pilots flying above the Stanfield VOR, particularly those using this waypoint as part of an instrument approach procedure, known as the “Stanfield Stack”.

The Stanfield Stack in action

The Stack consists of multiple airplanes, each separated by only 500 feet, holding over the Stanfield VOR and coordinating their descents to an initial approach altitude before beginning an approach into KCGZ.

Picture this: my instructor and I are on a training flight about to enter the hold at Stanfield for an instrument approach at KCGZ, but several aircraft are already holding over the VOR. Ten miles out, I hop on the CTAF to request “top of Stack,” a call that lets everyone know another airplane is joining them in the hold at the highest available altitude. The aircraft currently holding above all others reports their altitude, and we respond that we’ll be holding 500 feet above them. This repeats each time a new aircraft joins, with everyone listening and responding on time to keep the flow smooth.

As we arrive over the VOR, I enter the hold as specified by the ILS, RNAV, or VOR procedure we’ve chosen. When the aircraft at the lowest altitude (typically 4,500 feet) begins their approach, they report that altitude as open.

"N1234 taking approach altitude, 4,500 is open.”

That call sparks a virtual conga line of airplanes descending 500 feet, one at a time, each announcing the altitude they’re taking and the altitude they’re vacating.

“N5678 taking 4,500, 5,000 is open.”

It’s a beautiful symphony of coordination that allows for efficient use of the VOR and multiple simultaneous approaches.

Workload management in the Stack

As a student flying simulated IFR in the Stack, the workload is high. While flying the hold, I’m constantly correcting for crosswinds and drift while also keeping an ear out for the next altitude to open up so I can descend to the next rung of the ladder. On a typical day in Phoenix, the air grows hotter and more turbulent with each descent. Anyone who has flown during an Arizona summer knows that mixing unpredictable thermals with a 2,500-pound flying paperweight can make holding altitude, heading, and airspeed a constant orchestration of pitch, power, and trim adjustments.

After about 15 minutes of holding, it’s our turn to drop down to the initial approach altitude of 3,800 feet and begin the ILS 5 approach into KCGZ. The approach itself is straightforward: from the VOR, we descend 600 feet over the course of 2.5 miles until reaching glideslope intercept at 3,200 feet. But on this particular flight, there’s one more twist.

While we were in the hold, the wind at KCGZ shifted, requiring a circle to Runway 23. Our rate of descent increases with the tailwind, and we cover the 2.5 mile stepdown quickly. We configure for landing just before the FAF at ROXIE and follow the vertical guidance down to 2,000 feet, allowing a 40 foot buffer for the turbulence.

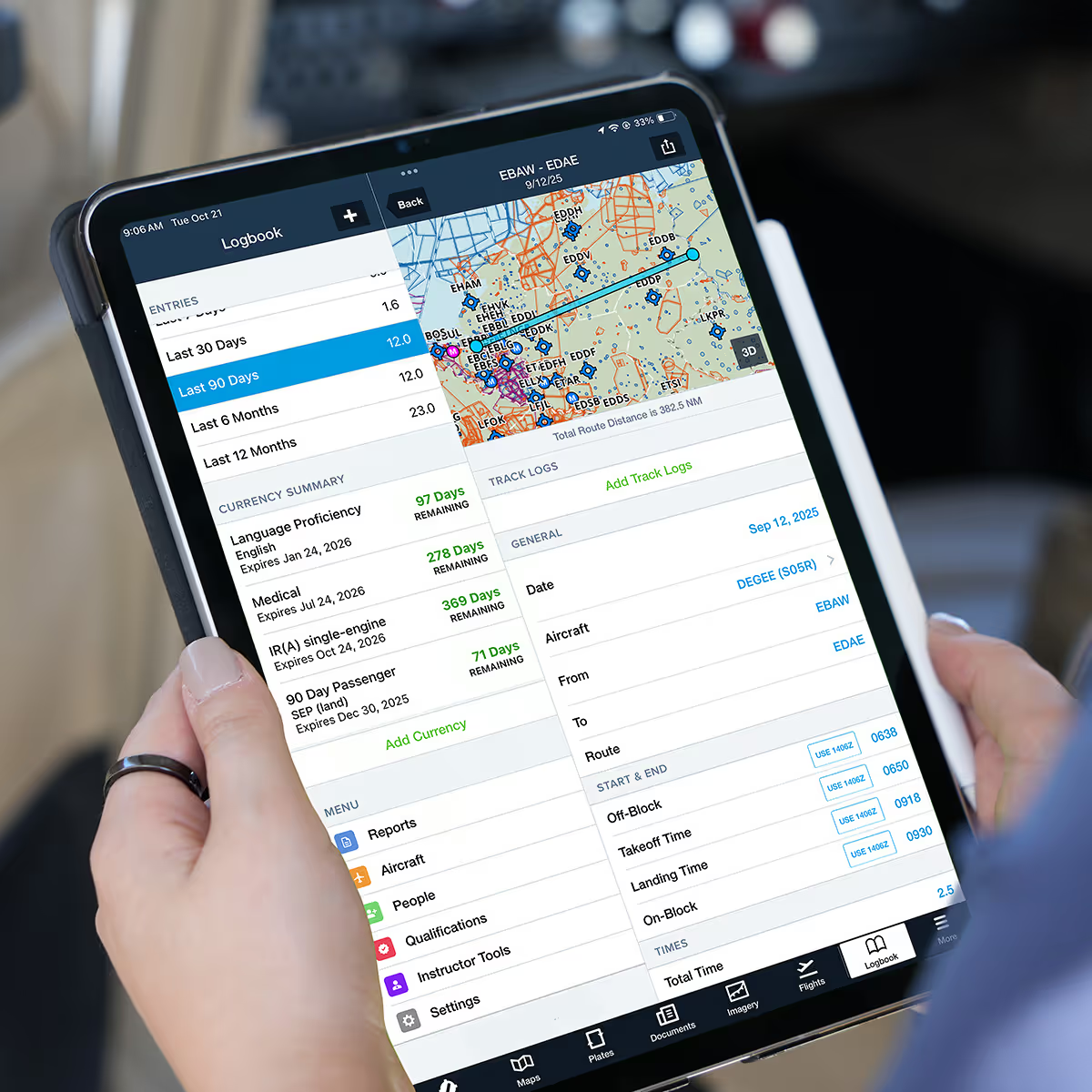

Flying instrument procedures with ForeFlight gives me several tools that help balance my workload under the hood. With the aid of Dynamic Procedures, a circling-radius overlay appears on the Map layer to increase situational awareness over my georeferenced plate, showing exactly when to begin my circle to the downwind.

Cross-referencing ForeFlight with my onboard avionics, I know I’m 1.3 miles out when I hear my CFI say the magical words, “Airport in sight.” I remove my hood, turn north, and enter a right downwind for Runway 23. On our turn from base to final, my instructor tells me that we’ve entered (simulated) IMC. I begin to execute the published missed approach, which, you guessed it, includes a hold over the Stanfield VOR. I get back on the CTAF request “top of Stack,” and it’s rinse and repeat as the process starts over again.

Just another typical day of instrument training in Arizona!